We see concrete everywhere. It’s ubiquitous in buildings, highways, infrastructure, sidewalks, homes, patios, and walkways. It’s cheap, strong and relatively predictable, but for too long we’ve collectively overlooked the cost of concrete: the human health impacts, the immense greenhouse gas emissions from its production, and the environmental consequences of our impermeable concrete world.

Emissions Associated with Concrete Production

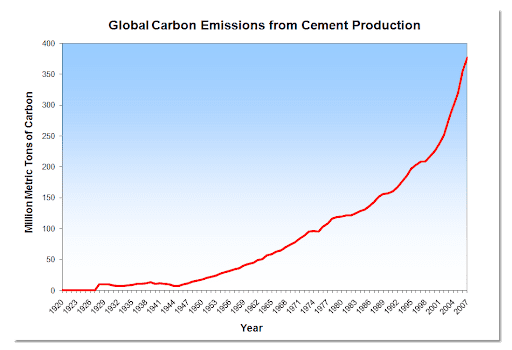

Concrete is made from aggregate (sand, gravel or a combination), water and cement. Creating cement is incredibly emissions intensive: for every one-ton of cement produced, one-ton of CO2 is emitted. That ratio is actually lower than some other materials like iron and steel, however given the prevalence of concrete the cumulative impact is great.

Shockingly, if concrete were a country it would rank third in the world of GHG emitters – right behind China and the US. It’s CO2 emissions amount to 8% of global anthropogenic emissions, an annual 2 billion tons! To put that in perspective, it is triple that of the aviation industry.

Concrete is the second most used substance on Earth, behind water.

Cement: Energy & Emissions Intensive

Globally, 9 billion tons of cement are produced annually, mostly for use in concrete

Limestone is a key ingredient of cement, and 2/3 of the emissions associated with cement production result from the calcification of limestone. That is, using very high temperatures to separate limestone (CaCO3) into lime (CaO) with CO2 as a byproduct.

The remaining GHG emissions associated with cement production are from burning fossil fuels and purchasing electricity.

Then, the lime is mixed with silica products (creating what is know as “clinker”) and finally with gypsum to make cement – Portland cement is the most widely used.

Silica, it turns out, is extremely dangerous as an inhalable dust, and some European countries have categorized it as a carcinogen. We’ll further discuss the human health impacts below.

Human Health Consequences of Concrete

Cement poses a number of serious health problems. Wet cement is extremely toxic and can cause caustic burns to the skin if touched – this is because of its extreme alkalinity (a pH of 12 or higher). Serious burns can occur if the cement exposure goes undetected and remains on the skin; some of these alkaline burns can even reach the tissue, muscle and bone.

Dry cement is dangerous as well. When cutting, drilling or demolishing concrete, silica dust or RSC – respirable crystalline silica – can be inhaled, severely inhibiting lung function over time. Silicosis is a condition where scarring of the lung tissue occurs from inhaling RSC, causing chronic wheezing, arthritis, cancer, and reduced life expectancy. RSC can also lead to asthma, pulmonary disorders, and kidney disease.

Environmental Impact of Concrete

As we mentioned concrete is a strong, relatively durable material. It is also impermeable to stormwater, contributing broadly the problem of polluted runoff and greater disturbance of aquatic environments.

Instead of designing landscape systems to capture valuable stormwater to percolate into aquifers, most development sought to pave, pipe and displace stormwater, letting it accumulate pollutants from industrial surfaces (concrete, asphalt, roofing) in the process. Most people do not realize that storm drains and municipal stormwater infrastructure does not treat the polluted water; it simply transports it – directly into streams and rivers. Stormwater pollution has vast consequences for our freshwater environments.

Furthermore, there is evidence that concrete itself can leach into the environment and raise the pH of the surrounding soil or water. One study found that freshly cured concrete (4 days or less) is most likely to leach – in one example, newly cured and installed culvert pipes raised the pH of the water around it to 11 (waters normal pH is 7). Vast fluctuations of pH have implications for the survival of plants and organisms that live in that local environment and are accustomed to more moderate pH levels.

Final Words on Concrete, Cement

Perhaps after reading this blog you also concur that concrete’s costs outweigh its benefits in most applications. At Green Jay Landscape Design, we’ve pledged to avoid using concrete as much as possible. The health risks from silica inhalation, the emissions associated with its manufacturing, and the direct environmental impacts from its impermeability make it a losing material in our opinion Stay tuned for our follow up post: GJL’s Ecological Hardscape Alternative to Concrete.

Contact us about your hardscape or landscape design project: 914-560-6570.